The Future as Fantasy

Konstnären och pedagogen Lucy Smalley reflekterar i sin text över framtiden som konstpedagogisk tema genom att jämföra och undersöka fyra olika arrangemang som ägde rum under Bästa Biennalen 2019.

In March of 2017 I launched the project ‘Sketches for an Unseen Future’ at Skissernas Museum in Lund. The project began as a collaborative drawing event where people of all ages and backgrounds were invited to the museum to sketch how they imagined the world to be in ten years time. Using an anonymous blind-drawing technique meant that everybody was unable to see their drawings whilst they were creating them, establishing a more level playing field between the five year old and the professional artist. This blind drawing method was chosen as a means for me to illustrate that when we visualise something as unknown as the future there can’t be a right or a wrong. If we can’t see the future then we don’t really need to see our paper either.[1]

At the time of writing this, almost three years on, it seems like this idea of the future is something even more precarious and out of our hands. News headlines about climate change, political turmoil and our collective impending doom are consequently encouraging us to question whether we even have a future. What were once light-hearted jokes about the apocalypse have now been replaced by hard scientific evidence that points to the bleak reality that we have made mistakes and will suffer the consequences. For many of us these changes may not happen in our lifetime. What does it mean, then, to ask the children of today’s world to think about the future? What is to be gained by asking them to respond creatively to the future within the frameworks of art? And what happens when we conflate a very real future point in time (albeit one inevitably different to the present) with an abstract, fantasy, anything is possible idea of the future?

The common interest in exploring the concept of the future within what I would like to call ‘art space education’[2] was palpable to me while looking through the programme for Bästa Biennalen 2019[3]. The exploration of the future within art and art space education is nothing new, but particularly now in our current climate this theme seems to have been given a new sense of urgency and educational relevance. I was interested to see how these urgencies could be represented within art educational spaces that are commonly associated with positive creative freedom and accessibility,[4] and if these affinities or demands[5] on art space education would limit the way in which the concept of the future could be presented or worked with.

Through studies, visits and interviews, I have collected information from four different art spaces in Skåne that participated in Bästa Biennalen in 2019, and that aimed to explore the future as a concept in one way or another through creative activities aimed at children and young people. The range of activities, perspectives and approaches were of course a reflection of the diversity of artistic production at each location, but these diversities also allowed me to compare how the future was represented, talked about and reflected upon across a variety of different platforms.

—

At Malmö Konsthall, visions of the future were grounded in a very real and tangible history, and in the understanding that what takes time to create can take very little time to erase. The exhibition The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (Room G) (14/09/19 – 12/01/20) by artist Michael Rakowitz dealt in a broad sense with preserving cultural heritage, documenting time, and unravelling cultural histories and conflicts. Reflections upon cultural heritage in the exhibition were political, and bound up in the context of conflict between the East and the West and the ownership of artefacts and sites.

The translation of these reflections within the educational space was predominantly achieved through a distancing from the heavy political realities in the Middle East and focusing instead on fundamental ideas of personal and local cultural heritage. The school project ‘Framtidens Kulturarv’ (The Cultural Heritage of the Future) was geared towards pupils aged between 10 and 14, and encouraged them to think about how we can represent the present by making a copy of an object or artefact in paper-mâché to preserve for the future. Here the future was an abstract concept that was explored through thought experiments and scenario building. Pupils were asked questions such as: which object would you want to be in an exhibition about 2019 in 200 years time; if there was a fire which object would you save; and which object do you feel represents our existence today. The activity required a more thorough consideration of the present than the future, but it still involved imagining how the future would be, what future generations would need to know or what they might be missing. The objects were vessels used to carry both personal and societal meanings, and not only took the form of physical objects but also immaterial ideas – for example a music note to represent a specific pop song or a love heart to represent love for their family. The pupils mostly interpreted the idea of cultural heritage as something personal to them or the city of Malmö; the task of representing humanity today as a unit in one object was harder to grasp and make physical. It was noticed that the younger pupils were more able to throw themselves into the act of creating an object without too much deliberation, whereas for older participants the thought process was more difficult. Perhaps here it was harder to detach from the realities of the exhibition’s context, and creation was inhibited by the perceived need to create something meaningful.

In our discussion about creative workshops at the Konsthall that corresponded to previous exhibitions with challenging political themes, my contact brought up a group exhibition entitled Speed 2 (2019) that broadly dealt with with the mentalities and unease of the Cold War. In many ways this exhibition solidified art’s duty to talk about difficult and unsettling subjects with the public, and these subjects were also taken into the creative workshop. I asked about how it was to work with these darker themes within the educational programme and was given the surprising response that it was actually a much more uncomfortable process for adults than for children. The exploration of these past references encouraged connections to be made with our present condition, which led to a sense of concern about the future.

Research shows that we largely construct our visions of the future through looking at the past. In professor Cristina Atance’s exploration of future thinking in young children, she notes:

There is growing consensus from neurophysiological and behavioural data that thinking about the future and thinking about the past are intricately entwined; our memories form the basis from which we construct possible futures. Young children (and arguably nonhuman animals) who are limited in their sense of the past will likely also show limitations with respect to the future. [6]

Without fully understanding the contexts and pasts that we are working from it’s difficult to expect the young people of today to have the same future-based anxiety as adults. Perhaps the reason why younger children were not so affected whilst working through difficult themes is that from their perspective the future is an adult problem. If they are at an age where adults take full responsibility for them, protect them and make their decisions, the future is perhaps not so much of a daunting idea. We discussed that the shift happens when children begin to take more responsibility for themselves, and are given the luxury of free choice over their own personal future. Future anxiety starts when we recognise that the future is a result of our actions or inactions.

Can it then be considered in any way unethical or unfair to present the realities of the future with younger children, and if not, whose responsibility is to present these realities? I began to wonder about the purposes and aims of art space education and the boundaries that it operates within.

Gallery and museum education are fields believed to have started in the 1960s and 70s in Europe and the USA, and regarded as institutionally based initiatives put in place through government schemes to operate on alternative grounds to conventional learning and to increase accessibility and inclusivity.[7] Working within the contexts of art and the organisations that celebrate it, gallery education as a continuation of art has come to be associated with the freedom that art, particularly contemporary art, is seen to have. As British artist and educator Felicity Allen wrote in her text Situating Gallery Education: ‘many gallery educators have built on ideas around the gallery as both publicly-owned and offering a philosophically ‘free experience’, of particular relevance to visitors who, like many artists, have negative or ambivalent reactions to conventional systems of authority.’ [8]

In a conversation that I had with a pedagogue at Skissernas Museum in Lund, it was apparent that the museum’s educational focus lies primarily on creating memorable experiences that children enjoy within this context of freedom. Participants are given opportunities to express themselves in the creative workshop and to work through different emotions using artistic processes, but it is also important that they walk away with a positive impression of the museum and an understanding that learning about art, and art itself, are both interesting and enjoyable. The museum pedagogue’s job is largely to encourage children to have a positive relationship with art so that art and art institutions are a part of their future.

I became interested in how these priorities could lead to the production of a certain kind of future image, and if it was possible to fulfil these priorities within the mediation of difficult or dark subjects. The exhibition …a borderless reality like gardens of the eternal… (04/10/19 – 02/02/20) by artist Carlos Garaicoa at Skissernas Museum takes its point of departure in the architecture of Garaicoa’s home city Havana, Cuba, the dense political and economic landscape that frames it and the ultimate failures of utopia. It is another heavy and challenging exhibition of brutal black and white photographic imagery of demolition sites, monochromatic architectural models, semi-abstract sculptures and a large amount of text.

The family workshop förändringar mot framtiden (changes towards the future) was connected to the exhibition and described as a chance to ‘fantasise freely’ about the future; it asked participants what kind of future visions they had and created a clear framework from which to work from. The activity was based on a photo series in which Garaicoa had taken photos of buildings that had been partly demolished and had then ‘rebuilt’ them through drawing over them. Taking these photographic works as a reference point, the workshop encouraged participants to think about how it could be possible to fix something that has been broken. I thought that in the light of today’s climate crisis this was rather prophetic, albeit unintentionally.

Despite this rather gloomy starting point the creative workshop was left open-ended with a positive spin. Using photographs of the city of Lund as it is currently, the focus was not just on how to rebuild something in a more interesting way but also to think about what we’re missing now and what would make it better. In a similar way to the workshop at Malmö Konsthall, the contemplation of our current world seemed to work well as a starting point in order to think about the future. Many of the participants on the day were under the age of five and so may have struggled if they were presented with the task of working from photographs they couldn’t relate to. Still, I was unsure about what it meant to show children these very real images of destruction and societal collapse and then invite them to a creative space where they are given the power to shape the future through play.

The Skissernas pedagogue responded that how we choose to respond to the past and the future really comes down to our reference points. When we as adults see images of destruction we link it to what we already know about crisis situations around the world that have happened or are happening; about specific contexts that are bound up in sadness or trauma. When young children see these images what kind of reference points do they have? Most young children don’t watch the news, and if they do they probably don’t understand the commentary. They don’t have the same criticality of society yet and, hopefully, aren’t old enough to have any kind of pre-existing relationship to these kinds of destruction images. Simply put we cannot assume that young children, particularly those who have grown up in a fortunate Western context, will respond to the past or the future in a specific way if they don’t have the necessary reference points.

We spoke about these questions surrounding agency and responsibility within art education and came up with another important perspective. It’s easy to think of the future as something that is ultimately out of our control and therefore conclude that we should be realistic with children about their future agency or lack of it. However, it is important to bear in mind that we don’t know whom these children will grow up to be. If we paint the future as we as adults see it now, something that we can’t influence or shape in any way on an individual level, we overlook the fact that these children could very well grow up to shape the future – locally or even globally. We need to remember that the future is largely people-focussed, and it is perhaps the responsibility of any educator, conventional or unconventional, to instil a questioning of how to make the world better now in order for it to be something that children prioritise in the future. This kind of thinking depends on the visualisation of future points in time and the knowledge of when the future begins on a personal level. It’s harder, however, to discuss the future in this manner when the future is presented in an abstract way.

Concepts of time were ambiguous in Ystad Konstmuseum’s exhibition På samma djupa vatten som du (In the same deep waters as you) (28/09/19 – 05/01/20) by the Swedish artist collective Gylleboverket. The exhibition was built up of three different room installations utilising objects, sound and video. The installations didn’t necessarily resemble a definite past or future but instead pointed to a time that was definitely not the present. This disorientating sense of displacement was in many ways dystopian, with videos of fire, barren landscape and references to ‘prepper’ culture, and yet nothing was defined or explained. The exhibition was introduced through a recorded text that visitors listened to with headphones on before entering the space; even this introduction and contextualisation was left open to multiple interpretations as it spoke poetically about our relationship to the natural world and to each other. This sense of openness within the exhibition unsurprisingly gave way to different reactions – in a guided tour for families, younger visitors stated that they felt both frightened and relaxed by what they experienced. Age didn’t seem to make a difference in whether they were frightened or relaxed, but again it seemed like this factor of reference points came into play. The music and sound within the installation was interpreted as both ‘scary’ by one child and ‘mysterious’ by another as the music reminded them of music in TV shows or films they had seen; Gylleboverket wanted the exhibition to generate many different feelings and emotional states, and this open-endedness and uncertainty was also taken through into the creative workshop.

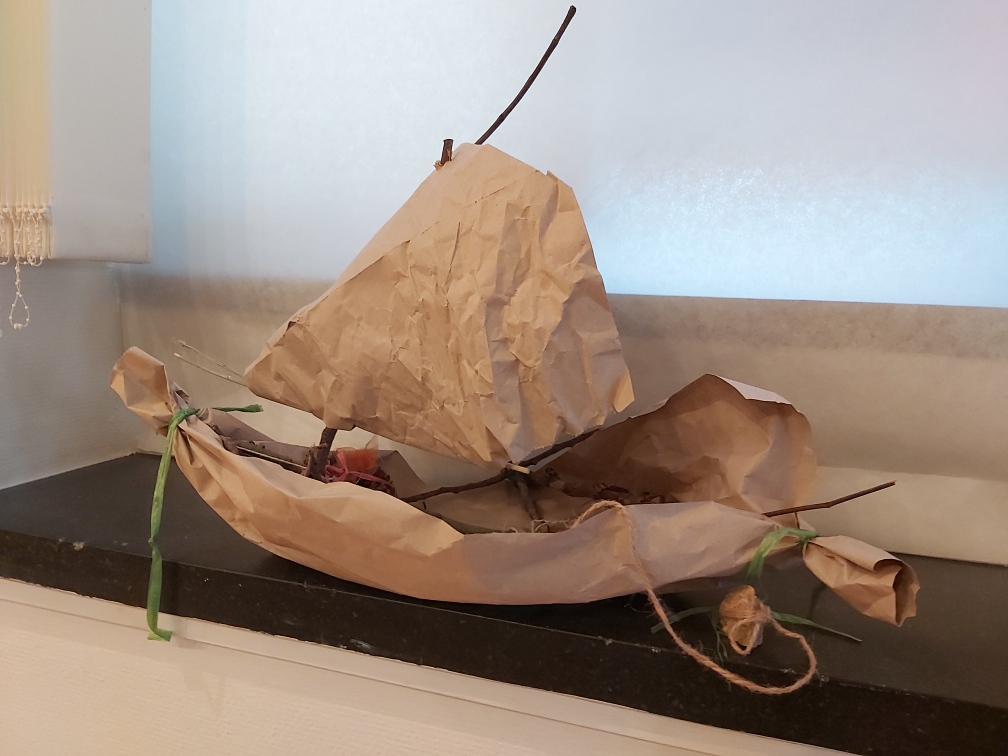

The objective of the task within the workshop was to create some kind of sculptural work, using a variety of natural materials that were also used in the Gylleboverket exhibition – wood, leaves, clay, sand etc. The workshop was not specifically framed for children to produce artefacts that either depicted the future or were from the future, but instead presented an opportunity for them to create something inspired by the exhibition with completely free reign over material choice.

Despite this reasonably open-ended framework with no specific intended outcome, the participants produced sculptures that were similar in their post-apocalyptic understandings of time. Many of the results were future-based, however they often depicted a future that was very distant to the maker and their envisioned lifetime. In this way, the more negative possibilities for the future were not something that they needed to worry about now. Subjects like ‘alternative humans’, ‘the rise of artificial intelligence’ and ‘the last fingerprint on Earth’ were extreme and based upon apocalyptic or at least semi-disastrous situations, but this fantasy future was not something that seemed to be a direct threat. Rather the opposite, as possibilities for the future were treated as a kind of fantasy fiction – one young child in the workshop quite happily worked on their sculptural model of a second Noah’s ark flood and the global destruction that this would cause. To see this behaviour was slightly worrying in some ways because it reminded me of our adult denial of the future and the tendency for disaster containment; of sweeping away possible or even likely future problems because they are not problems now, and therefore ultimately failing to solve them. Children’s understanding of the future may well be connected to their understanding of the (occasionally fictional) past, but can their attitudes towards the future be solely driven by what they already know?

Following on from Atance’s findings that future thinking is connected to our past experiences, she continues:

Despite this proposed overlap, research findings also suggest neural differentiation between thinking about the past and imagining the future, which may be due to the fact that future events involve some novelty (Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2007). This view echoes that of Haith (1997), who noted that humans do not just base their future thinking on past events but can also ‘‘imagine and create things and events that have never occurred before’’. [9]

Even if we use art space education as a place to try to be more realistic with children about the future, is it worth conveying a sense of urgency? Or, going even further, worth letting them know that responsibility will ultimately fall into their hands and preparing them to be solution orientated?

At Osby Konsthall in the north of Skåne, the future and the part that mankind will play in it was an overarching theme during Bästa Biennalen. This subject of the future was decided on by the municipality management for the whole culture sector to work with in the area, and had the aim to ‘increase faith in the future’ amongst children and young people. It was decided upon in the light of a new children’s rights law that was to be introduced in Sweden in January 2020, giving equal rights and opportunities to all children in Sweden.

The exhibition En dröm om framtiden (A dream about the future) (19/10/19 – 04/12/19) was split into three parts within the Konsthall under the exhibition time period. The first part took the form of two interactive artworks created by the artist Ulrika Wennerberg; philosophical reflections upon our relationship to the future that functioned as a backdrop or conceptual base for the exhibition. The second was a growing collaborative exhibition of artworks, texts and objects created by school children that reflected their visions of the future, and the third part was the results of a workshop that happened during the opening of the exhibition where participants were encouraged to write a letter to the future.

Brev till framtiden (A letter to the future) gave participants of all ages a chance to respond creatively to the exhibition in the Konsthall through the act of letter writing. They could write about how they envisage the future to be or write a letter to their future selves, and could choose whether they wanted the envelopes to be left open or sealed. If the letter was sealed it would remain sealed, and they could collect the letter from the Konsthall at a later date, whereas if it was left open it was seen as an invitation for others to read. All of the letters, open and sealed, were displayed in the exhibition space. Within this framework of semi-concealment the task produced similar outcomes to what I experienced with Sketches for an Unseen Future, with reasonably clear distinctions between how different ages responded. Younger writers/drawers described a more fantasy future – they wanted to live in houses made of sweets and to be given horses for free. Older children over the age of 10 were more interested in issues surrounding the environment, renewable energy and our local society. The adults who wrote letters more often than not wrote about the bigger picture. They wanted world peace, to end racism, and to live in a world where everyone is loved.

The collaborative collection part of the exhibition at Osby Konsthall happened through inviting children and young people to reflect upon the idea of the future at home or at school, and to bring an object – an artwork or a text to the Konsthall to be displayed. Children were given a few ideas of varying ambiguity for inspiration, for example: ‘how can we solve environmental problems?’; ‘how will we live in the future?’; and ‘how long is the future?’

These reflections took numerous forms as different schools responded to the task in different ways but responses were generally very concrete in their ideas. One school group created 3D cardboard houses that they would want to live in in the future, whereas the drawings from one school group pictured how individuals saw themselves or their lives in the future – the activities they want to do or their future careers. As I noticed in the responses at Malmö Konsthall, personal futures were much easier to reflect upon creatively than global ones. Researcher Annika Elm came to the same conclusion when she looked into the views of four to six year olds in Sweden and found that ‘whilst they had problems thinking globally, they were well able to talk about their personal futures and that of their local community.’[10]

The purpose behind these activities was foremost to encourage children and young people to pay attention to the future and to inspire visitors through giving them the opportunity to encounter different perspectives about the future, but it was also a way to show children that their thoughts are both valid and valuable. It was explained to me that the Konsthall wanted to respond to the children’s rights law change by reinforcing a sense of positivity about the future; to use the workshop as an open and safe space in which confidence can be built and where it is possible to discover a sense of personal perspective.

While empowerment, freedom and security are common goals of art space education, what happens when largely unrealistic dreams and visions are temporarily given the spotlight? This situation reminded me of the aims of urban development and the obligatory ‘social research’ that takes place when planning a city. When citizens are given a welcoming platform for idea generation and told that their ideas are valued only to see none of those ideas materialise in reality, it creates conflict and distrust. It feels often like the time, voices and energy of ordinary people are used solely by those with power in order to tick the box of community collaboration and goodwill.

Of course the crucial difference in this situation is that we are talking about an abstract time, and that those working with art space education have very little influential power over the bigger picture. It’s perhaps difficult to see any sort of future-changing power in the physical results of an art workshop, and it could be regarded as wrong to tell children that their dreams of the future made visible in drawings and 3D cardboard models have the power to influence and make a difference. However we can’t rule out the possibility that this power or value might instead lie as a by-product in the individual who has the dream, and that empowerment is maybe grounded in a new sense of awareness made possible only through this opportunity for creative engagement.

—

A while ago a friend told me that when he has children he wants to be honest with them about Father Christmas from the very beginning. He said he wouldn’t want to play along with the grand illusion and wouldn’t want this ‘deceit’ to become grounds for his children to doubt what he says about other more important things in the future.

What happens when we tell children that their future is anything that they want it to be and that any discussions about the future are opportunities to fantasise freely? Or, as in this last example, when we tell children that they have all the power they need to influence and make a change?

To begin with, there are huge differences between how children of different ages view the future. The examples in this text show that there is no great danger in exploring the concept of the future and all its possible outcomes with small children, as it is difficult for them to conceptualise or to think clearly about the long term. Even if we wanted to nobly replace the presentation of a fantasy future with the harsh realities we wouldn’t achieve very much, as young children are likely to separate themselves from this future time regardless. Whereas with older children and teenagers who have access to news headlines and seem to feel a similar existential crisis to adults, there is probably more to be gained from realist thinking and it is important that they are given a space in which to air their concerns and respond to them creatively.

As researcher Richard Eckersley wrote about 15-24 year olds in Australia after studying the differences in expected and preferred futures:

It might be argued that people have always had visions of an ideal world and these have always been beyond the reach of reality. What is important, however, is whether the gap between the ideal and the real is perceived to be widening or narrowing. A belief in progress demands that the gap should be closing; the findings of this and other studies indicate that the dominant perception among young people is that the gap is getting wider.[11]

Just as there is a crucial difference between ages, we also work from our geographical context and living standards in our perceptions or visions of the future. What does the future look like to those who have to walk for miles to the nearest source of running water? Their concerns about the future will certainly be very different from ours.

Even within the first world, I began to wonder if the global sense of future is an elitist problem. Those who already know that their personal futures are safe must have a greater possibility to think more seriously about the world’s future – taking the famous contemporary example of Greta Thunberg and her inherited position of power as the daughter of celebrities. It is after all those born into privilege who are more likely to be in positions where they are able to impact the systems affecting the future – whether it be through politics, business, trade, etc.

Do those who experience anxiety and uncertainty in their personal future even have the possibility to worry about the global concept of future and take action? Or are their future worries bound up solely with their own survival? The privileged have the benefits of time, freedom and stability, but arguably also the responsibility to use their time for the greater good while others are not able to.

Within the advantaged contexts that art spaces often occupy, it seems like there are many positives that can come out of engaging with the subject of the future. As researchers Hicks and Holden claim, ‘What children and young people need is guidance on how to think more, rather than less, critically and creatively about the future, whether personal, local or global.’[12] Hicks and Holden were talking here specifically about the school education system, but I would argue that in many cases art space education is a more likely place for criticality and creativity to be combined, and combined successfully. When talking about the future with children we need to make use of the freedom of art space education to question Eckersley’s gap between the ideal and the real, and, if relevant, use the opportunity to encourage children and young people to think about their own personal goals and the role that they could play in a collective future.

It seems that what we can take from this is the importance of defining time where it is possible, and therefore either strengthening or deliberately weakening the link to realism. There’s nothing wrong with asking children to design the city they would want to live in or describe what they want to be in twenty years time. If the future is truly unknown then we can’t close off the possibilities of it, but within art and art space education we need to continue to ask questions and present the future as a time in flux.

There is a freedom in the art world that allows for expression of visions and dreams without boundaries. If art is regarded as the place that isn’t limited or policed and where there is no ‘wrong’ answer, then surely art space education can also be a place where the future is discussed both realistically and fantastically.

Notes:

[1]www.sketchesforanunseenfuture.com

[2]Art space education is used here as my own umbrella term to include all public spaces working with art pedagogy and/or socially engaged art – from the permanent museum to the temporary art space or cultural centre.

[3]Bästa Biennalen is a contemporary art biennial for children and young people that takes place in Skåne every other year.

[4]The issues with these associations and their ultimate effects were cleverly discussed by Tom Morton in his article ‘Are you being served?’ in Frieze magazine, Issue 101, September 2006.

[5]Governmental funding demands on gallery education in the UK also highlighted in Tom Morton’s text. Ibid.

[6]Cristina M. Atance, Future Thinking in Young Children in ‘Current Directions in Psychological Science’, University of Ottawa, Volume 17, Number 4, Pages 295 – 298, 2008.

[7]As discussed in a text by Felicity Allen about gallery education in the UK and also in a text by Anna Lönnquist about the local art education network in Skåne, Sweden:

Felicity Allen, Situating Gallery Education in ‘Tate Encounters [E]dition 2’, 2008.

Anna Lönnquist, Skånskt nätverk för konstpedagogik, Ystad Konstmuseum, 2012.

[8]Felicity Allen. Ibid.

[9]Cristina Atance. Ibid.

[10]Annika Elm, Young children’s concerns for the future – a challenge for student teachers. Paper presented at a conference on ‘Children’s Identity and Citizenship in Europe’ (CiCe), Riga, May 2006.

[11]Richard Eckersley, Dreams and expectations: young people’s expected and preferred futures and their significance for education in ‘Futures, 31 (1)’, pp. 73-90, 1999.

[12]David Hicks and Cathie Holden, Remembering the future: what do children think? in ‘Environmental Education Research’, 2009.